–Spoiler alert, conclusion at bottom

Opinion by Mathew Carr

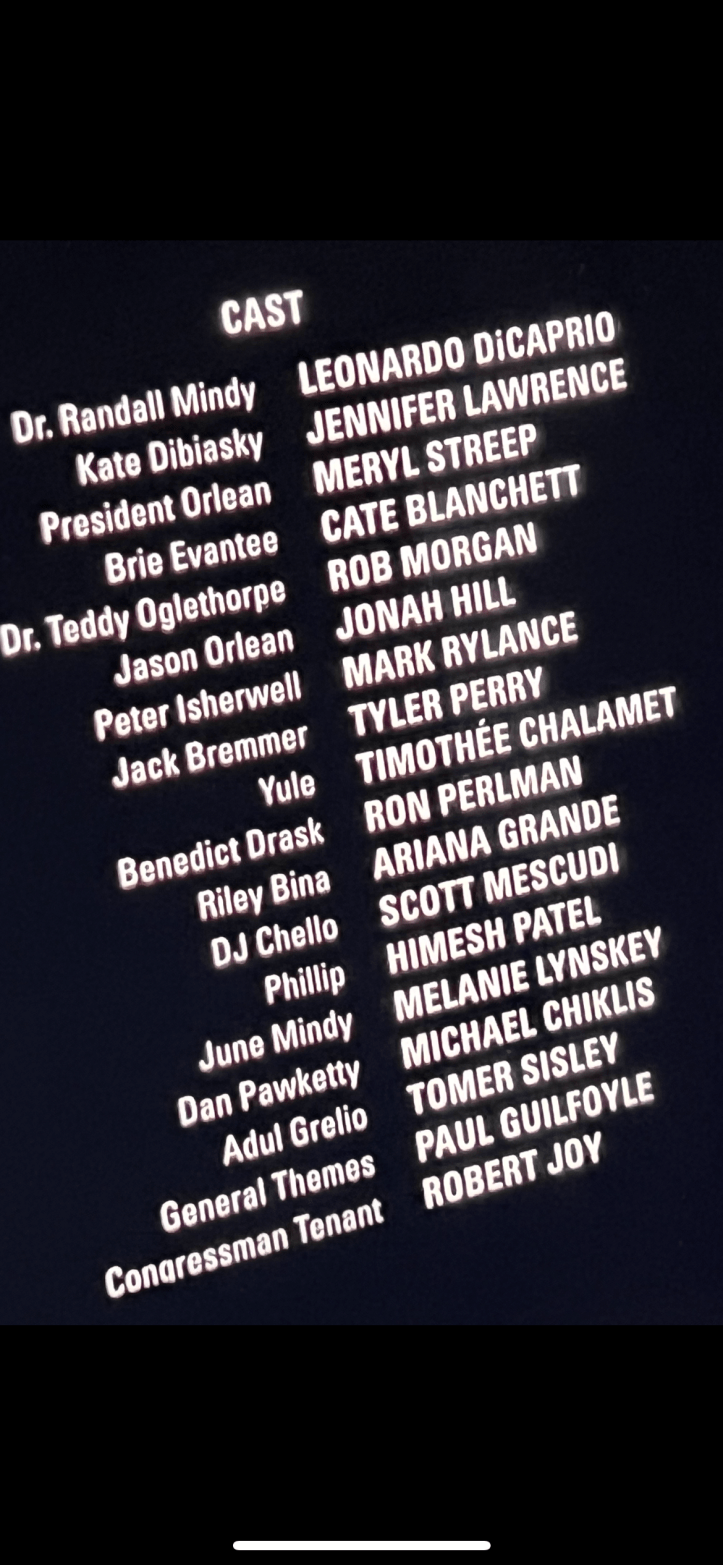

Dec. 31, 2021 — I watched Leonardo DiCaprio’s latest film in a state of absolute, undiluted awe.

Maybe I’ll be mocked for the rest of my life for writing this, but the movie made me feel much less lonely, after fighting in various hearings and courts my “fair” dismissal from Bloomberg News, more than 19 months ago.

Scene after scene, the instant-cult-classic “Don’t Look Up” mocked the tsunami of cultural and political bullsh!t driving much of the world’s flippant attitute to science and the environment (and the associated short-term thinking). It was just what was needed to make a little sense of everyone’s shitty 2021.

Six Stupids

One — Scientists are dismissed / mocked / treated with disrespect (see how DiCaprio’s Dr Randall Mindy is treated by politicians and the media, and how he’s portrayed in the movie, periodically, as the villain)

Two — Women are victimised (See how Jennifer Lawrence’s Kate Dibiasky — who actually deserves the credit for the comet’s discovery more than Mindy — is treated by the President’s son. I’m sorry to say I did laugh at times at the outrageous behavior of son Jason Orlean played by Jonah Hill. Jason, who writes speeches for the fictional governing U.S administration from the “saving Private Ryan” movie script, is one of the best villain characters ever invented in Hollywood movie history … and I don’t say that lightly.)

Which brings me to Three — The satire applies a large blowtorch at the world’s rampant materialism. As the risk of world obliteration becomes more acute, Jason also gets possibly some of the best lines in Hollywood movie history:

“I also wanna give a prayer for stuff. There’s dope stuff, like material stuff, like sick apartments and watches, and cars, um, and clothes and shit that could all go away and I don’t want to see that stuff go away. So I’m going to say a prayer for that stuff. Amen.” The “pleasure seeking activists”, on the other hand, are demonised by the establishment in a bid to hide its own culpability.

Four — U.S. politics and inequality are showcased. Meryl Streep plays an absolutely terrifying President Orlean. Think President Trump with even less self awareness (Yes, it’s possible). Of course, there are characteristics portrayed in the film that could apply to a few of the world’s G20 leaders (as well as the leaders of some smaller countries, to boot).

Five — Short-termism is laid bare. Instead of trying to deflect the comet and save the world, the satirical U.S. seeks to split it into multiple pieces so it can grab hold of the $140 trillion of mineral (and other mysterious) assets contained within the bits.

Six — Selfish geopolitics are exposed. The fictional president and a fictional tech billionnaire cut Russia, India and China out of the key deal for the rights for the comet’s minerals. An attempt by the emerging nations to deflect the comet’s landing fail amid a giant explosion. “I am not on one side or the other. I’m just telling you the fucking truth,” Mindy says at one point, criticising the U.S. plan.

I feel some empathy with Mindy, who in the film faces ridicule and contempt, as well as hostility from the establishment.

I, of course, step into his shoes in a limited way.

I’m not arguing my efforts reach anywhere near the level of DiCaprio’s climate-action push.

I’m also not saying that Bloomberg LP is near as dysfunctional as the “Don’t Look Up” splattering sh!t show.

But it clearly has its dysfunction and there are certainly some parallels with my own efforts over the past decade or so.

Luckily, I also have a few friends and contacts to help set a little useful context.

See this Tweet sent a couple of days ago from credible climate scientist Glen Peters:

In the chart, Peters is relating the fictional comet hitting earth in the film to a 1.5C temperature rise.

He quite rightly notes it’s far-from-perfect comparison.

Obviously a temperature gain of that measure since pre-industrial times is not quite as visceral as the speeding hunk of rock (unless you understand the potential consequences of feedback loops such as melting icecaps and escaping tundra methane, like Peters does).

But, a disaster is a disaster, even if it’s a slow-onset event. The film plays out over six months while my experience was over more than six years:

I started covering carbon markets and climate change as a journalist for Bloomberg News around 2003 after being headhunted by the firm in 2000 from the Australian Financial Review in Sydney.

After transferring to London, my main beat was natural gas and even oil-producing companies, for a while.

As carbon markets began and then briefly flourished for a while earlier this century, I was regarded by my employer as a star.

2010

In my 2010 performance review, my leaders said this: “As we expand the number of editors and reporters focussed on carbon news I would like Mathew, as the senior reporter on the beat, to think about how we best allocate our resources and explain such ideas to his team leader and other managers so that we can agree on how we proceed through 2011.”

2011

My interim review from 2011 included this from my managers:

“Would like to see if Matt can become a panelist/moderator at carbon conferences in order to further promote Bloomberg, and his own readership and influence.”

After the end of 2011, this from my managers: “Distinguished performance on Bloomberg Values including an Excpetional perfomance in terms of Customer Focus as Matt demonstrates that he is an agent for his readers, not his sources.”

Bloomberg had become a carbon-news force.

I said this at the time:

“Continued focus on customer needs has helped us win terminal business. It’s gratifying to hear that [major oil company]’s carbon desk has switched to Bloomberg from Reuters, for instance … We continue to miss opportunities to break news in carbon in regions around Europe and the world.”

Little did I know it at the time, but I was already nearing my apparent peak. The carbon markets, which force polluters to pay for the emissions they produce, didn’t fire up as expected, and the global financial crisis and messed-up politics distracted politicians away from climate protection in the period from about 2011 to 2016.

2012

At the end of 2012, I was sent by Bloomberg LP to help cover the climate talks in Doha, Qatar. Nations scrambled to extend the Kyoto Protocol by another eight years – to the period from 2013-2020.

The talks were regarded as another failure. See this summary from Climate Home News

Bloomberg didn’t seem to understand the importance of the failure – my managers didn’t at least. It started to hit my psyche.

I began to complain that we — that is the media organisation and my team, and me specifically — were not doing the right thing and not being incentivized and rewarded properly for what we were doing.

I realise the exploitation of labor is par for the course in large (Amercian) global companies — but the extent of the exploitation is still hard to take when the discourse is “We always do the right thing.”

I said this in my annual performance review: “I’ve had a good year, most tellingly demonstrated by the boost in my byline hits by 68 percent … Most weeks we influence prices and I aim to try to better measure that during the next year. I was involved in eight most influential stories, compared with 2 the previous year (granted we now count them better).”

2013

By 2013, I was pushing back about where I was being told to direct my efforts – fossil fuels:

“I’m increasingly frustrated by the lack of editing capacity…

I thought [a key editor] was brought here to do carbon…yet he’s done more fossil than carbon lately … but I also get frustrated when I get put on UK gas news after 13 years of it.“

OK my frustration was at a much lower level compared with Mindy … yet it was palpable and debilitating.

2014

I continued to push back on managers’ statements that climate negotiations did not get good readership so should be downgraded for coverage:

“Yes climate negotiations and carbon markets are a can of worms…but we need to open that can, dive in and report what’s wiggling,” I said at the time.

“While we may be world beating…we can do so much better. The management decision to shift [a key reporter] to coal was in hindsight a bad one. It is clear we need better coal coverage…but to take it from the area providing the solution to climate change is perverse in the extreme. We need more reporters covering the nexuses between energy, climate policy and the markets…so market failure does not continue to win the day.”

2015

By 2015, I was getting into trouble for trying to write about the global climate picture, including in North America. See this snip of a story, which was corrected on the Bloomberg terminal (but not on the Website until much later — managers still won’t say when it was corrected on the Bloomberg website. That’s one of the many things being covered up and it was probably a deliberate attempt to set me up to fail):

As of late 2021, the USA is still considering including a carbon price policy of some sort into its economy, but it has not done so yet at the federal level.

I wasn’t sent to cover the Paris climate talks, yet I managed to help break news on them from London, with the help of long-term contacts among ranks of negotiators, other well-informed people, colleagues and editors. See this snip:

2016

Despite breaking that story and many others, I was placed on my first performance-improvement plan in 2016.

Under the UK whistleblowing law (as I found out after being dismissed in May 2020), a “qualifying whistleblowing disclosure” means any disclosure of information which, in the reasonable belief of the worker (that’s me) making the disclosure, tends to show that the environment has been (1), is being (2) or is likely to be damaged (3).

Note – it can be any one of the three options. And note – it does not say the damage needs to be being done directly by the employer (in this case Bloomberg LP — one of the most influential firms on earth when it comes to capital allocation).

Secondly, whistleblowing case law requires that the information being disclosed is specific enough (caselaw known as the Kilraine test – see page 22 here) – in my case I contend it must show enough information to Bloomberg LP so that my employer should have known how it could help limit damage to the environment in the future.

Yet, the employment tribunal and the Employment Appeal Tribunal have so far struck out some of / all of my alleged whistleblowing.

Here are some examples where I clearly do both the required things in my alleged protected disclosures:

May 2016

I said this: “As the climate crumbles, I was expressly told by [team leader at the time] to write fewer carbon stories, but there was no clear direction about what I should otherwise do.”

Here I was saying to the human resources representative at Bloomberg that the climate is crumbling (the environment is being damaged) and that the direction I was being set in (ie to write fewer carbon stories) was the opposite direction to one that might have helped limit damage to the environment (ie MORE carbon stories).

I said: “A view that power-network stories aren’t in demand is plain wrong.”

Here I was saying to Bloomberg LP that should we write MORE about power networks and the need to electrify the economy – move it away from fossil fuels – then investors might have had a better chance of limiting damage to the environment.

Yes, I was assuming some knowledge by my employer — that was reasonable, I contend.

I said: “Today’s energy story is wrapped up in climate protection, and whichever news company properly covers in a regular, systematic way the damage that each new fossil fuel project will cause … into energy-investment stories etc … will lead the market, because there’s so much intriguing tension in that. The media companies that understand the wastefulness of spending $200 a ton to cut emissions via offshore wind farms now when today that sum will probably cut 10 tons via a coal-to-gas switch … will become rich.

“Our coverage is too focused on fossil fuels without the important climate context and I believe we should be writing more about climate protection when pretty much all the governments and our clients are asking for carbon pricing…publicly anyway.”

Here, I was being somewhat technical, but still clearly meeting the above tests.

The phrase “climate protection” by itself shows I was talking about limiting damage to the environment. Yes I was sweetening my message by talking about how my suggestions might be good for Bloomberg LP (but just because I’m doing that does not cross out the environmental protection message).

“If a country spends $200 to cut 1 ton of carbon dioxide when the same money could cut 20 tons then that means there is an extra 19 tons of heat-trapping gas in the atmosphere that need not be there.”

I was pointing out the importance of cost-efficient climate action because every extra ton in the atmosphere is doing damage. I was saying that if Bloomberg LP highlights this urgent need for less wasteful climate policies, then damage to the environment could be limited. This is clearly specific-enough information and my employer could have and should have recognized it as such.

Let me spell out why the last paragraph is whistleblowing. Adding climate context into fossil-fuel stories would probably have meant more hesitation by investors investing in coal, crude oil and natural gas. That’s specific enough.

Oil companies were already asking for carbon pricing (and had been for years, at least in public).

I was saying that we at Bloomberg LP were ignoring that message and we were therefore indirectly causing the damage.

Carbon pricing means polluters would need to pay when putting heat-trapping gas into the atmosphere.

Having to pay gives oil companies and utilities an incentive to try cleaner energy systems. That information that more carbon pricing stories were needed was specific enough to allow Bloomberg LP to seek to help limit damage, had it been inclined to do so.

Later in 2016, I was taken off the performance improvement plan, having “done enough” to improve my performance. I had earlier hired a lawyer to help me navigate the process.

2017

In early 2017, I continued to “blow the whistle,” or so I thought, like Dibiasky and Mindy did in “Don’t Look Up.”

I set out what I said then in this earlier story: My Alleged Whistleblowing to Bloomberg’s Head of News That ‘Wasn’t Specific Enough, Not in Public Interest’

Basically, I wanted Bloomberg LP to improve its climate news coverage, something it didn’t really do. It did so superficially in about 2020. It’s still not as good as it knows it should be, I contend.

2018

In 2018 my performance metric counts surged. That didn’t stop my managers from periodic harrassment (as well as help at times too — I’m not one eyed about this situation, which included highly sophisticated performance management.)

2019

By February 2019 I was one some type of “headcount” reduction roadmap (redacted here below). The senior newsroom manager who had me on it was meant to be available for cross examination at the trial, but Bloomberg decided not to call him. I contend more evidence of a sophisticated cover up.

Headcount Roadmap

In the middle of 2019, I was placed on another performance improvment program (PIP) immediately after again complaining about Bloomberg LP’s climate coverage. This time I listed concerns on the firm’s outside “ethics / whistleblowing” hotline.

Bloomberg managers decided to place me on the so-called PIP on July 12, but didn’t tell me.

My big mistake was allowing human resources officials to turn my attempts at collaboration using the hotline to improve “our” climate-news product into a “grievance”.

That’s when I became a threat rather than a collaborator. If you are blowing the whistle, don’t let them do this.

A few days after the decision to place me on the PIP, I contend in order to create more evidence against me, the managers gave me a “sham” warning for insubordination, after I complained because the Financial Times beat us on the story about how the appointment of Ursula von der Leyen as President of the European Commission might boost the European carbon market (Bloomberg could have won on the story, but was focused on managing me out rather than looking after its customers).

Indeed, the insubordination allegation was particularly Don’t-Look-UP-esq crazy.

As part of my enquires about the politics at the time, I obtained important quotes from Mark Lewis, who was then Head of Sustainability at BNP Paribas. My view was that the story was important and should be published by the end of the day to prevent a competitor breaking it.

Editors disagreed with my assessment and refused to publish, alleging it wasn’t finished.

Consequently, the Financial Times published a very similar story a few minutes later – after we’d gone home or around that time.

I was subsequently issued with the verbal warning for insubordination after highlighting the loss to managers with an emailed “smile”. My manager initially refused to specify what I’d done wrong, demonstrating the concocted nature of the warning.

I covered some of the alleged whistleblowing around this time (June and July 2019) in this story: OPINION: Bloomberg LP Fired Me, a Climate Whistleblower; Someone Needs to Probe Mike’s Soul (1)

I didn’t find out about the PIP until late August, almost two months after the decision had been taken.

There were numerous warnings, appeals, investigations, shams, I contend. It seemed like a sort of time-wasting circus.

2020

Following the protrated, debilitating process, in May 2020 I was fired for not being capable enough. I have so far lost the argument that I was fired because I blew the whistle.

________________

Conclusion

Unlike DiCaprio’s character in the movie, I’m not dead. Well, not yet anyway.

I never got hit on by a glamorous TV executive in the shape of Cate Blanchett.

Nor did I get invited on an intergalactic flight to escape a collapsing planet.

I never stood in the middle of Bloomberg’s fancy London headquarters and accuse President Trump of being a freaking loon, even though a few of my colleagues probably thought about doing something like that.

I never said this on a popular TV show, like DiCaprio’s Mindy did:

“If we can’t all agree at the bare minimum that a giant comet the size of Mount Everest hurtling its way towards planet Earth is not a fucking good thing, then what the hell happened to us? I mean my God, how do — How do we even talk to each other?”

To be sure, I also never loudly screamed “fuuuck” like DiCaprio’s Mindy did when he realised all was pretty much lost.

But what I tried, and evidently failed, to do, was convince my managers that treating the climate crisis as a crisis was not activism.

I contend that what I wanted to do wasn’t non-neutral journalism at all.

Indeed, the striking of the Paris climate deal in 2015 made what I wanted to write about truly “neutral.”

It was the right thing to do. That’s what I said when I asked the initial judge in my case to review his initial decision that went against me, back in July 2020.

Pursuing news that buttresses the status quo, that’s activism, I contend. And it’s not activism in a good way.

(More to come)

NOTES:

My court case is subject to review / appeal. Search for “Bloomberg” on the CarrZee.org homepage for more stories on the dispute.

See this DiCaprio Tweet for his commentary about the film and the climate crisis:

[…] a Bigger Climate Villain Than Fossil Fuels; BBC Worst, for Misleading For About 24 Years: Monbiot I’m an Ever-So-Slightly Uglier Leonardo DiCaprio, Formerly of Bloomberg News Humiliated Again by the UK Legal […]