–Bloomberg Commodities Index is Overweight Crude, Adding Turmoil to Already-Rigged Market

–BCOM Weightings Blow Out Index’s Fossil Fuel Limit

–Other Commodity Indexes Are Even More Heavily Weighted to Fossil fuels

By Mathew Carr

Aug. 2-30, 2021 — (LONDON): The Bloomberg Commodities Index, a key index for funds tracking exposure to energy, agriculture, metals and minerals, is exceeding its limits for crude oil, boosting demand and further magnifying price shifts in an already-rigged market.

No commodity is meant to exceed 15% of the BCOM index. Yet, adding together Brent crude and West Texas Intermediate crude’s weightings, they equalled 17.91% in June, the latest data available according to Bloomberg’s website (see note 2). They’ve been exceeding the limit most of the year.

The energy segment’s weighting in the index, all fossil fuels, was 35.41%, 2.41 points more than the supposed upper limit and more than 5 points more than the target (see weightings chart below and link in caption for methodology).

Commodity indexes, which are surging, are meant to give investors a way to expose themselves to the market prices of the building blocks of the global economy, yet so much money now follows them they themselves also can drive price movements and underpin damaging biases in economies, according to people who know.

One key area of concern for regulators is the conflicts of interests of the investors and administrators of indices.

“Risks arise from incentives stemming from conflicts of interests, which may be amplified when expert judgement is used in benchmark determinations,” says the International Organization of Securities Commissions (whose membership is made up of national regulators) — see note 6.

IOSCO is looking into these conflicts through the end of 2021. See its work program document for this year and next — see note 11.

The organization has “launched a review of conduct-related issues in relation to Index Providers. In

2020, it surveyed its members, and in 2021 it will further engage with stakeholders to explore

issues related to the role of asset managers in relation to indices and index providers and the

role and processes of index providers in the provision of indices (including the potential impact

of administrative errors on funds and identifying potential conflicts of interest that may exist at

index providers in relation to funds). The findings of this work will be delivered in a report to

the IOSCO Board in late 2021.”

Commodity and oil Exchange Traded Funds were some of the riskiest at the start of the pandemic, IOSCO said in a new report published about two weeks ago (I just noticed today, apologies). See this: https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD682.pdf

“In April 2020, prices of oil futures were subject to high volatility (including falling to negative prices), which triggered concerns that the continued holding of oil futures for certain futures-based oil ETPs/ETFs might lead to a substantial or total loss to investors. In view of this, the managers of many of these ETPs/ETFs decided to implement a temporary change of investment strategy, such as an accelerated rollover to replace the oil futures contracts with longer term contracts, with short notice to investors,” IOSCO said.

Certain derivatives-based ETPs/ETFs that were impacted by extreme market circumstances may warrant further consideration related to product structuring and contingency planning, IOSCO said.

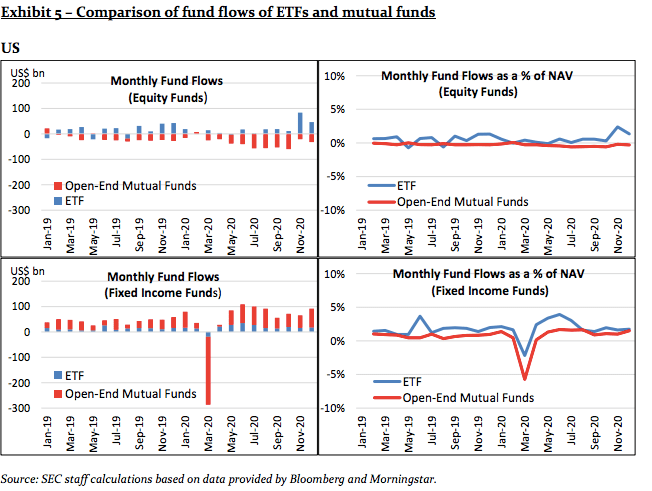

Fixed income funds had outflows of $500 billion in March last year, including almost $300 billion in the U.S. alone.

Gushing

It’s true, sophisticated investors know about many of the risks.

Here is one bank’s suggestion from earlier this year for how commodity investors might deal with the climate transition:

Credit Suisse marketing note from February said this: Shunning commodities may have adverse consequences for performance, create unwanted market volatility (on a macro level) or potentially undermine new technologies. We think the way forward is to internalize emission costs from production and consumption related to commodity sourcing and extraction.

A promising approach, in our view, is to add carbon offsets to direct commodity investments. For this purpose, tradeable EU emission allowances provide a suitable instrument and can be added and scaled to commodity baskets (like our benchmark, the Bloomberg Commodity Index BCOM).

See note 7. I added emphasis.

Looking forward, unless investors carefully read the fine print (and of course they all do!), they may not realise they are:

i) helping to lock in the status quo/climate inaction by underpinning polluting commodities;

ii) potentially missing out on higher returns offered by clean-tech industries, and;

iii) exposing themselves to risk when the index managers finally do update their methods.

Commodity indexes “need to be disrupted,” said one senior trader at a giant U.S. bank.

To be sure, BCOM flags that its weightings can blow beyond limits in between yearly “rebalancings,” so investors should be aware.

After the Libor index scandal, the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority admitted it should have done better, partly because there were weaknesses in the design of benchmarks and how conflicts of interests were overseen. “As we saw with Libor reference rates, for longer tenors in particular, these reference rates had failed to evolve with changing markets.”

The world is continuing the painful process to extract itself from the flawed Libor and will probably continue to do so through 2023. So that will be 18 years from when the bad behavior took place to final solution. The intensity of climate crisis means the world does not have that time to deal with any problems at commodity indexes.

I’m not claiming knowledge of bad behavior at Bloomberg’s index unit, but the parent organization’s conflict of interest is clear. Based on the structure of the U.S. economy, Bloomberg probably makes about $1 billion of its $10 billion plus of yearly revenue from fossil-fuel-related business. (Bloomberg doesn’t publish the figure as far as I can see and it also makes plenty of sales from cleantech and green markets.)

I asked Bloomberg to detail who exactly was involved in overseeing BCOM. It didn’t answer with specifics (see below for unanswered questions section).

Section One: Different takes on economic building blocks during the climate transition

Commodity indexes and exchange traded funds have very different structures. They number more than 100 and probably cover hundreds of billions, if not trillions, of assets under management (I’m struggling to find a specific number). A fundamental point is that they not only track commodity pricing trends, they also influence prices because the amount of money investing in the space has increased as investors add to tracking funds.

Investors seeking alternatives to bonds, stocks and property see commodities as a way to diversity and limit risks, especially as economies recover from the pandemic as governments shovel vast quantities of financial support into markets.

For instance, if a bank accepts an investor’s cash to track an index, a logical way to hedge the risk of offering that product would be to buy futures or options contracts that match the weighting in the index, a purchase that impacts real markets. BlackRock, the world’s biggest investor, offers at least one product that tracks BCOM. See note 9.

Back in 2013, the impact of indexes on physical commodity prices was not seen as a huge problem as commodities jumped after the global financial crisis, but indexes do impact markets, especially as futures contracts roll. See note 8.

Bloomberg did reply to a few of my questions relating to BCOM’s structure and its relevance during the climate transition:

Q: Can you explain why these over-weightings have occurred – this has been happening most of this year?

A: BCOM weights float throughout the year based on price movements of the underlying commodities within the index – they are not fixed at their target weights. Under Diversification in our docs it states “diversification rules have been established and are applied annually”. For the annual rebalance which takes place during the January roll period, Crude Oil Target Weights were WTI 8.144832% + Brent (6.855168%) for a total of 15%.

Q: Do we define Brent and WTI as two different commodities?

A: Crude Oil Weight = Brent and WTI

Q: Are the overweight ratios related to production/trading volumes only … i.e. is it automatic as per the methodology?

A: The uptick in weights for Crude Oil are attributed (to) the price movement of all commodities within the index. In particular, the movement of both Brent and WTI (~50% YTD).

Q: Are Bloomberg managers or other people involved in setting the weightings in between rebalancings, or only at rebalancings? Can you say which people are involved at Bloomberg Index Services Ltd., and which committees? How are the committees decided?

A: Bloomberg Index Services Limited (BISL) is responsible for determining which commodities are tested for inclusion. BISL hosts an annual Bloomberg Index Advisory Council (IAC) which affords a cross-section of participants, including, asset managers, asset owners, and dealers the opportunity to offer feedback regarding Bloomberg indices (e.g., BCOM) and related services. The Council is for advisory purposes only and has no decision-making power or function. Bloomberg decides unilaterally whether, and how, to respond to any feedback, comment, or recommendation that results from the Council. Target weights are determined by the defined rules in the index methodology.

(See note 3: the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority lists some managers of BISL) [End of q and a]

The FCA declined to comment on whether BCOM’s administrators were doing anything wrong and on whether the commodity indexes were structured appropriately.

BCOM Energy Weighting Jumped to 35.4%, Well Above the 2021 Target

To be sure, the BCOM’s weightings for fossil fuels are far less than other indexes, demonstrating each managers’ assessment of which commodities are most important.

The Refinitiv/CoreCommodity CRB Index, the world’s oldest, also says it acts as a representative indicator of today’s global commodity markets. It measures the aggregated price direction of commodities and comprises a basket of 19 commodities, with 39% allocated to fossil fuel energy. See also note 4.

The S&P Goldman Sachs Commodities Index is weighted more than half fossil fuels:

Also, coal is not tracked, despite its continued very important role in providing energy around the world.

Other sections of the BCOM methodology seem out of date. See this:

“Production Averaging Period” means the most recent five-year period for which world production data for all Index Commodities are available as of the applicable Calculation Period. For example, the Calculation Period for the determination of the CIPs (commodity index percentages) for the calculation of the Index for 2021 (i.e., 2020), the Production Averaging Period comprises the years 2013 to 2017, inclusive.

See questions section below.

For context, here’s why the indexes are doing well: As economies grapple with reopening their economies during the pandemic and after massive government support programs, hedge funds plowed money into bets that the commodities rally of 2021 still has further to run, snapping three straight weeks of reductions, Bloomberg reported some of this July 30 (see note 1).

For instance, net-long positions on a basket of 20 commodities rose by 8.3% in a week near the end of July, according to U.S. Commodity Futures Trade Commission data compiled by Bloomberg, said the report. Investors added wagers on further price gains for raw materials including crude oil, natural gas, corn and copper, while cutting those for platinum and soybeans.

Companies involved in fossil-fuel supply chains have been raking in profits.

Some of the biggest fossil fuel producers are even planning expansion, apparently partly based on commodity-price performance as the global pandemic progresses.

It seems to me, commodities markets as we know them are under structural pressure, especially in the period beyond the pandemic recovery (or even in the remainder of this year — see note 5): The market for crude oil is already deliberately rigged because the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) plus Russia limit supply to boost prices and profits.

Meanwhile, most countries have spent trillions of U.S. dollars subsidizing fossil fuels to stoke economic production, for more than 100 years. That’s brought on the climate crisis and the need to rebase the global economy to a different system.

Judging from the past 30 years, that system could still take years to evolve, yet the underpinnings for cleantech are simultaneously being reinforced. While only about a fifth of global heat-trapping gas contends with a carbon price, those prices are mostly so far too low to limit fossil fuel demand very much and encourage business into cleaner tech. That’s so far blunted the need for reform of the commodity indexes.

Maybe a simple name change would be a useful first step, to save people from being misled: Traditional Commodity Index, maybe?

Surging oil prices may still be temporary (or not), and may even have some benefits on top of encouraging alternative energy.

“A period of strong profits and cash flow will make it much easier for international oil companies and national oil companies to make the transition to clean energy while keeping investors on board,” said Tim Williamson, a former senior official in the U.S. government, in a post on LinkedIn. “This is their one shot. For everyone’s sake, let’s hope they do not blow the opportunity to switch before investors walk.”

High oil prices will also ease the transition for countries currently relying on fossil-fuel money and they may even be a condition of support for the Paris rule book being negotiated this year. The nature of the UNFCCC means consensus is required for a global deal.

Section Two: Old economy, new

Bloomberg and others offer environmental, social, governance indices and clean-tech indices for those wanting to track clean commodities. That’s certainly true.

Indeed, the copper weighting in BCOM is somewhat of a proxy for the increased demand for electricity — as economies electrify, they need wires and the copper to make them.

See this chart for a comparison of BCOM’s performance against other indices/trackers:

BCOM is the black line. The yellow line is the Kraneshares Global Carbon Exchange Traded Fund that tracks carbon markets. The blue line is an electric vehicle index. The red line is a LME copper contract.

Copper wins over five years, while carbon wins over the past year, even beating electric cars (as at the end of July).

Yes, electric cars are not a commodity, although under a broad definition they might be construed as a building block of the new economy.

And so there’s the rub. Just how dated is the current world’s notion of a commodity? What about rare earths needed for batteries and renewables? See this:

With a 38% gain in the past year alone, it’s clear BCOM-tracking investors have done well. Yet, that’s a small gain relative to KRBN’s 73%.

I’ve asked Bloomberg whether it’s considering adding carbon to BCOM. It declined to comment.

That brings us to the final section.

Section Three: What happens next ?

BCOM says it’s meant to provide “liquid and diversified exposure to physical commodities”. That begs the question I’m asking. Six years after the Paris climate agreement was struck, why hasn’t it and other commodity markets diversified already, or at least begun to do so?

The index has evolved, for sure. For instance, from December 2018, its methodology and tables were updated to reflect inclusion of low sulphur gas oil. So incremental change is already happening, related to environmental protection.

I’ve had no luck so far finding out how quickly the BCOM methodology might change going forward, if it changes much at all. But some of the language in its 101 page methodology should make investors using it pay attention:

Index and Data Reviews

The Index Administrator will review the Indices (both the rules of construction and data inputs) on a periodic basis, not less frequently than annually, to determine whether they continue to reasonably measure the intended underlying market interest, the economic reality or otherwise align with their stated objective. More frequent reviews may result from extreme market events and/or material changes to the applicable underlying market interests.

Also note this:

“Any discrepancies requiring revision will not be applied retroactively but will be reflected in the weighting calculations of the Index for the following year.”

(I added the emphasis)

The questions that the index managers face are fairly existential, as it becomes increasingly difficult to place the climate transition into its own silo.

An article by GraniteShares in September (see link in caption of snip below) compared BCOM and S&P GSCI, concluding: “Any investor would surely concede that petroleum is a more important commodity than coffee, but by precisely how much? Is it eleven times as important as per weightings in the BCOM index, or eighty-five times more significant as the GSCI index would suggest?”

To that question, managers and investors need to ask not just “by how much” but also “for how long?”

What happens to index methodology, for instance, if there’s a major climatic event, which seems increasingly likely, and if governments around the world are forced to quickly implement much higher carbon prices to speed the transition?

I contend the commodity indexes as we see them now could quickly become much less fit for purpose.

QUESTIONS-ASKED SECTION (INCLUDING THOSE NOT ANSWERED):

Questions to Bloomberg. I published responses received above, where I got some:

Just also wanted to ask this in a follow up question…why a ~four-year time lag here (p43 of the 101 page methodology)?:

“Production Averaging Period” means the most recent five-year period for which world production data for all Index Commodities are available as of the applicable Calculation Period. For example, the Calculation Period for the determination of the CIPs for the calculation of the Index for 2021 (i.e., 2020), the Production Averaging Period comprises the years ******2013 to 2017, inclusive

Earlier:

I’m interested in things that seem to be working against climate protection … and the apparent pro-fossil-fuel structure in BCOM is interesting from that frame.

I do realise high oil prices can help the energy transition by making crude less attractive …and also that BCOM’s copper content is a proxy for demand in the electricity industry, for instance.

I was hoping to get a better understanding about how the BCOM numbers are decided between rebalancings and at rebalancings.

Given the world is seeking to wean itself off fossil fuels for more than three decades and especially since the Paris climate deal was struck in 2015, is the methodology appropriate/up to date? Is the current BCOM structure making the climate crisis worse? Why/why not?

Should the index include EU carbon allowances – has that been considered? why/why not?

What about clean energy/electricity?

What if anything has been considered for the index to reflect the energy/climate transition? Was that considered at the last rebalancing and when was that?

~~~~~~~~

Questions to the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority (not answered):

Is Bloomberg doing anything wrong here with the overweight fossil fuels?

Earlier:

The FCA regretted not regulating Libor properly. See this: https://www.fca.org.uk/news/speeches/do-i-need-worry-about-benchmark-regulation

See this especially: But there were also weaknesses in the design of benchmarks. As we saw with Libor reference rates, for longer tenors in particular, these reference rates had failed to evolve with changing markets.

Given that, can I please talk you into commenting on this story: http://carrzee.org/2021/08/02/buyer-beware-commodity-indexes-lock-in-dire-climate-status-quo/

Is the FCA concerned if an index repeatedly runs weighting above the maximum stated? Isn’t it possible people are being misled because they are not checking the data every month?

Is the FCA concerned the indexes are too heavily weighted toward fossil fuels and allocating capital inappropriately and slowing climate action?

Shouldn’t companies managing indexes name all people influencing decisions on weightings/balancings/methodology so to better ensure they are managing conflicts of interest properly?

Is this already a requirement?

IE …I think Bloomberg makes about $1 billion a year of its revenue from fossil fuel-related business. How does the FCA ensure executives overseeing BCOM are not boosting the weighting of fossil fuels in the index as a favor to its customers?

There’s a similar potential conflict at S&P for the S&P Goldman Sachs Commodity Index, for instance, right?

~~~~~~~~

Disclaimer:

The author has an ongoing employment dispute with Bloomberg News, over his performance plus blowing the whistle on the quality of its climate-transition coverage. I covered energy and carbon for about 18 years for Bloomberg through May last year. I worked for Bloomberg News for almost 20 years. Please let me know if you think any of this above seems biased in any way at mathew@carrzee.net

(Adds IOSCO report from Aug. 12; materials Tweet, smooths language slightly, updates with more IOSCO, FCA no comment, questions section for transparency.)

NOTES

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-07-30/hedge-funds-are-plowing-money-into-commodities-once-again

- https://www.bloomberg.com/professional/product/indices/bloomberg-commodity-index-family/

- https://register.fca.org.uk/s/firm?id=0010X00004KQp6CQAT

- https://www.refinitiv.com/content/dam/marketing/en_us/documents/methodology/cc-crb-index-methodology.pdf

- https://assets.bbhub.io/promo/sites/12/1266450_BCOM-August2021Outlook.pdf?link=button-body

- https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD415.pdf

- https://www.eticanews.it/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/3.CreditSuisse.pdf

- https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w19065/w19065.pdf

- https://www.blackrock.com/us/individual/products/227418/blackrock-commodity-strategies-inst-class-fund

- As of Aug. 11, the most recent “monthly” fact sheet on Bloomberg’s website was dated June 30

- https://www.iosco.org/library/pubdocs/pdf/IOSCOPD673.pdf